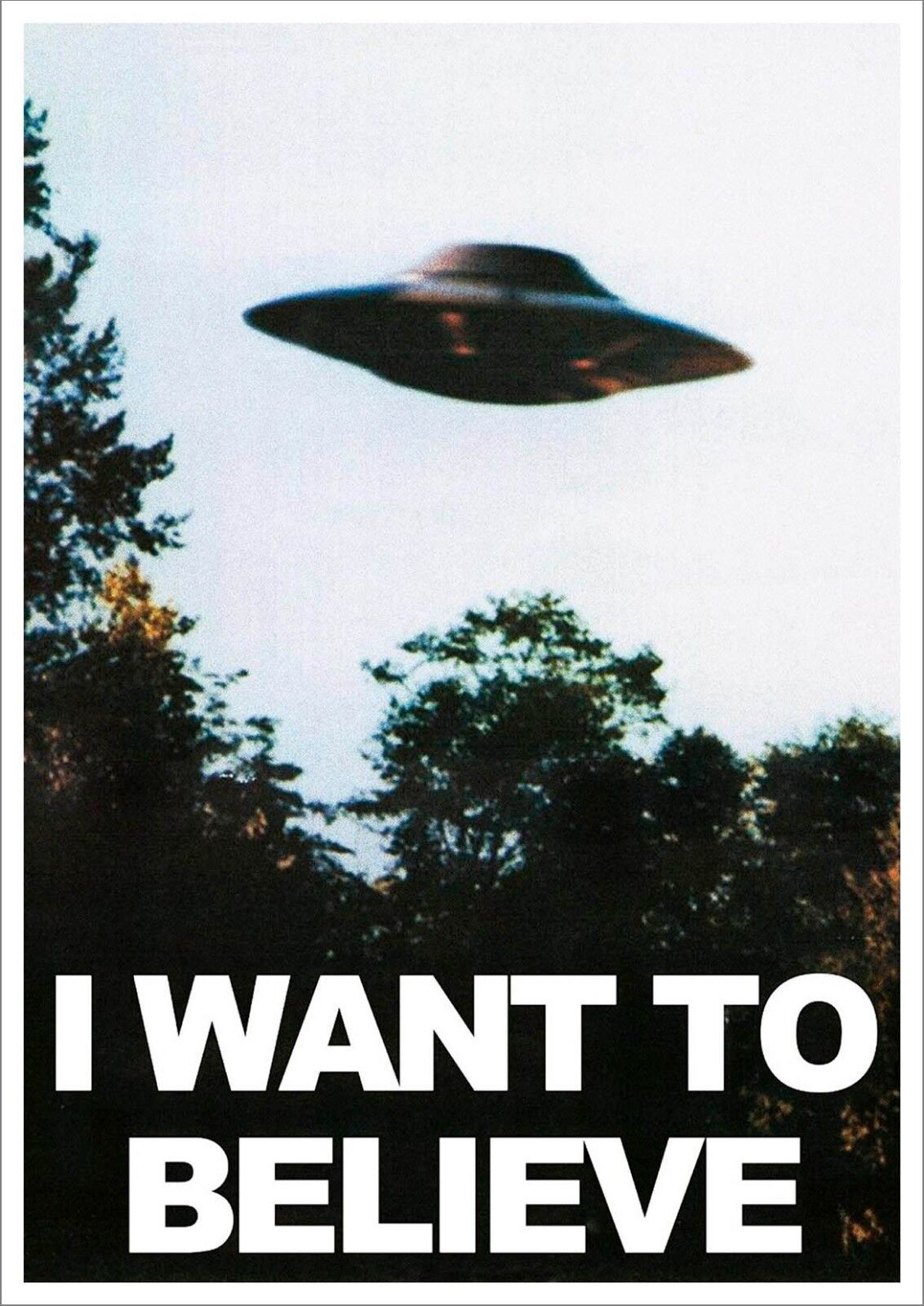

“I want to believe.” That phrase may elicit thoughts of UFO or paranormal investigators, or perhaps someone with a crisis of faith. Many would probably not be willing to publicly utter such a phrase, for fear of being thought of as “less than logical”, or even a nut.

The truth of the matter is that, people, as logical as we like to think we are, are very gullible. The criminal justice system, the economic system, medicine, and even science in general is far more susceptible to accepting nonsense than most of us appreciate. This willingness to accept nonsense as fact is all based on an innate human desire to think that (sometimes unknowable) truths can be divined from expert opinions, statistics, AI or some other means.

Experts are a great thing to have. In general, we call in an expert when we’ve reached the end of our ability to perform or understand something important. These experts often have decades of experience in a field of study we have little knowledge of. Most of us probably have experience with a trusted doctor an excellent mechanic, or some other expert. These people have likely solved some problems for us and enabled us to go on living our lives when we might have had a serious disruption without them. In the case of medical doctors, you can see how something like a small stent can seemingly cure many heart ailments. It’s easy to want to believe that doctors, or at least some doctor, somewhere, has the answer to basically any medical issue. Although these experts are a great resource, their answers aren’t always “a sure thing” and don’t really constitute undeniable truths. One thing is for sure, when it comes to life and death, most of us are willing to take a doctor’s advice. We want to believe they can help us.

Many experts are called on to use science to supposedly prove guilt or innocence in the criminal justice system. Jurors listen and defer to experts who claim that “dental records match” and that the odds are “1 in a million” that this evidence would match another person.. Many of these fields of study (bite mark analysis, bullet casing/firearm matching, bloodstain pattern analysis, lie detector tests), are not definitive and involve analysis where many experts reach different conclusions with the same evidence. Jurors may even be told that this analysis is not infallible, however, jurors often convict people based off of expert testimony over their own knowledge of the evidence. Expert testimony is easy to defer to when you’re asked to make a decision based off facts you don’t understand, however, expert evidence almost never includes analysis of other facts in the case. Thankfully, many legal and scientific groups are proving that many of these fields of study are junk science. Reliable DNA evidence has, in recent years, allowed many of the results of these dubious methods to finally be disputed definitively. Sadly, we’ve want to believe that experts could help us deliver certain justice, even when other facts didn’t line up with the expert opinion.

You can start to see we humans want to have the answers to tough issues, even issues we’re individually unqualified and unprepared to address. In these cases where we clearly do not possess an answer or ability to resolve the issue on our own, we want to believe that an expert, a system, or some method can provide the answer for us. In these times, we often turn to another crutch– the internet, a book, or some other resource that promises to distill millions of indecipherable pieces of information together into a single, easy to understand concept that we can take action on. These sources can be compilations of expert opinions, statistical analysis, or even worse, simply popular opinion. To the layman, a book full of expert opinions is like listening to a doctors advice without letting them examine you — it’s even less definitive than an expert opinion. Statistics are a tricky thing– human bias or “blindness” often influences statistics in ways that undermine their use in any particular situation. Many statistics come with a disturbing number of caveats which, if not known, can lead to huge problems. Can DNA evidence prove whether a person is the father of a child? Yes, unless the parent is a twin or a chimera (has 2 sets of differing DNA), or if the child is a chimera. Many books have been written about the abuse and misuse of statistics. Suffice it to say, if you’re using information or statistics that you don’t fully understand, you’re likely fall prey to the tendency to think you know more than you actually know.

As Benjamin Franklin once wrote, “The doorstep to the temple of wisdom is a knowledge of our own ignorance.” As an individual, recognizing our own ignorance is not an impossible task, however, recognizing the ignorance of society and our systems is much more difficult. How can we know if the next drug is safe, when the same system and people approved “fen-phen”? How do we know if ballistic evidence is reliable when bullet casing evidence has been disproven? How do we know there’s a hole in the ozone layer, and whether or not that’s important, and what the cause or cure for it is?

In my own life, I’ve had to be comfortable with answering many of these these questions with “I don’t know”, or “I choose to believe…” Very few things in life can I claim to know for absolute certain. My hope is that we can remove the stigma that seems to be associated with admitting that we don’t have all the answers. I hope we’ll use this realization of possible ignorance to fill the gaps.. to dig in and research a bit more, or to at least admit that we don’t really know for sure and that we’re choosing to believe something that we can’t necessarily prove. I think that when we do this, we’ll have a better social discussion, we’ll respect other people more, and we’ll continue to learn more about ourselves, those around us, and the world we all live in.